What's Cooking? Crab Culture

Dean Tyrus Miller shares his recipe for crab cakes and knowledge about crab culture in Maryland. Click to read more and also see the Cooking with the Professor video with Dean Miller and Professor Deanna Shemek.

In my home city, Baltimore, the blue crab is an essential part of the food culture, especially in hot weather. On humid Baltimore summer evenings, it’s typical to bring home crates of live crabs for steaming or grilling, and to accompany them with crab cakes, spicy crab soup, cole slaw, potato salad, and of course lots of cold beer. You assembled the family and friends in someone’s backyard, spread portable tables with newspaper, and dumped the crabs out for a long, messy feast as the sun set and the fireflies started flickering in the grass.Crab culture has an ancient history in the Chesapeake Bay area of Maryland and northern Virginia, and the crab cake was already part of the cooking culture of the indigenous Piscataway and Powhatan peoples long before European colonization began in the 17th century. These indigenous ways of preparing the seafood of the region were adopted by the first European colonists as well.

Throughout the 18th and 19th century, crabs and shellfish constituted an important food source for the growing cities of the East Coast. Even before the Civil War, black “watermen”—freed slaves—were key to this development. In his Narrative of the Life, Frederick Douglass imagines the waterways of the Chesapeake Bay as his route to freedom: “I will take to the water. This very bay shall yet bear me into freedom. The steamboats steered in a north-east course from North Point. I will do the same…” After the Civil War, the Chesapeake Bay became the most important source of crabs and oysters for the eastern seaboard and African American workers predominated in the crabbing and crabmeat canning industries, even as they were increasingly subjected to oppressive segregation in work and everyday life.

The 1920s and 1930s were crucial for modern crab culture, establishing certain features that continue to this day. First, in the 1920s, the competing New Jersey crab habitats were exhausted and almost all crab fishing shifted to the Chesapeake Bay (a similar shift from Maryland waters to the Gulf of Mexico has occurred more recently). The real and symbolic connection of Baltimore with crabs was sealed, particularly before refrigerated trains and trucks allowed this highly perishable food to be more widely transported. Second, in 1928, the modern wire crab pot was invented by Benjamin F. Lewis, allowing a larger harvest than the old fashioned “trot line,” a baited cord used to haul crabs up from the water. This technological advance allowed a significant expansion of the crab “harvest,” at least as long as pollution and destruction of habitat had not yet decimated their population.

In the late 1930s and 40s, the “crab cake” as a branded recipe—its actual existence as a food item dated back centuries!—came into its own through its inclusion in the World’s Fair Cookbook, published in connection with the 1939 World Fair. It is part of my own family’s lore that my grandfather, grandmother, and mother drove up to New York from Baltimore for a few days to visit this optimistic spectacle pitched on the edge of World War II. Underpinned by the spread of refrigeration and the success of published recipes, the Maryland crab cake came onto the menu in more and more restaurants and kitchens across the United States and eventually even internationally.

On a more intimate note, 1939 also saw the invention of the famous crab spice-mix Old Bay Seasoning, by a German refugee in Maryland named Gustav Brunn. Now distributed by the major spice company McCormick (founded in Baltimore in 1889), Old Bay can be readily purchased in grocery stores. If I had to point to a deep family “tradition” of the crab cake, it would be, I confess, that of following the reliable and tasty crab cake recipe on the back of the Old Bay Seasoning can!

Tyrus Miller

Recipes shared by Deanna Shemek

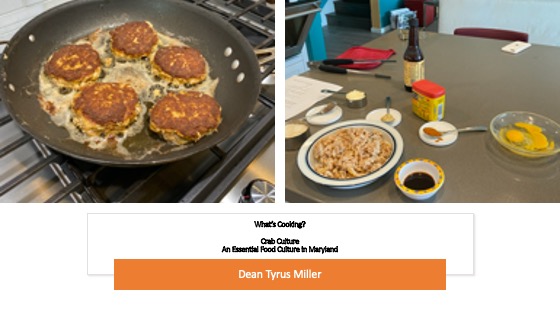

Maryland Style Crab Cakes

SERVINGS 3-4

YIELD 6-9 cakes

- 1 lb lump crabmeat

- 1/2 cup breadcrumbs (I use panko)

- 2 eggs

- ¼ cup mayonnaise (do not use dressing)

- 1 teaspoon Old Bay Seasoning

- ¼ teaspoon pepper

- 2 tablespoons Worcestershire sauce

- 1 teaspoon prepared mustard

- Mix together eggs, mayo, OLD BAY, pepper, Worcestershire sauce, and mustard, until creamy.

- Add bread crumbs, mixing evenly.

- Add in the crab meat, being sure to mix evenly.

- Shape into cakes.

- Makes 6 large or 9 medium crab cakes.

- Sauté in pan with a little oil for about 5 minutes on each side.

- You can also broil them until brown. This may require you to flip them, depending on your pan.

- Serve with tartar sauce or lemon, or just plain. They really don’t need a thing.

- One head cabbage, sliced into shreds or processed in food processor using the slicing blade

- 3 carrots, grated or processed in food processor using the grater blade

- Generous shakes of white wine vinegar

- 1/2 teaspoon salt or to taste

- Sprinkling of your favorite seed (I used caraway and celery seed for this)

Variations: Seasoned rice vinegar and a dash of toasted sesame oil for a more Asian flavor. Other vegetables are also good with the cabbage or instead of it, including turnip, rutabaga, celery root, kohlrabi, daikon, beet.

Oven Potato Chips

- Slice unpeeled potatoes about 1/8 inch thick. Yukon Golds or other yellow potatoes work well. Dress them with olive oil or avocado oil and sprinkle with salt or another desired seasoning.

- Spread potatoes in one layer on a non-stick baking sheet and bake at 425 Fahrenheit (some say 450) for 15-20 minutes, turning once. Keep an eye on them to watch for desired browning, because ovens and potatoes vary. The potatoes should come out crisp, like chips. Even if they don’t, they will be delicious.

Click to watch Dean Miller and Professor Shemek on Cooking with the Professor!